“Six people were killed or injured by strangers in the sanctity of a private home. Several children lost parents. Many families were devastated. The community’s sense of security was shaken by the apparently random nature of the attack.”

— Justice Colleen Suche

Time passes. It’s pretty obvious, I guess, that people can and do change.

But when it comes to those who commit the worst criminal acts, it’s natural to wonder: ‘Do they really? Can they?’

That’s the major question looming today, exactly 11 years after a senseless triple homicide rocked the city and sent multiple families into dealing with staggering loss and trauma.

That’s the major question looming today, exactly 11 years after a senseless triple homicide rocked the city and sent multiple families into dealing with staggering loss and trauma.

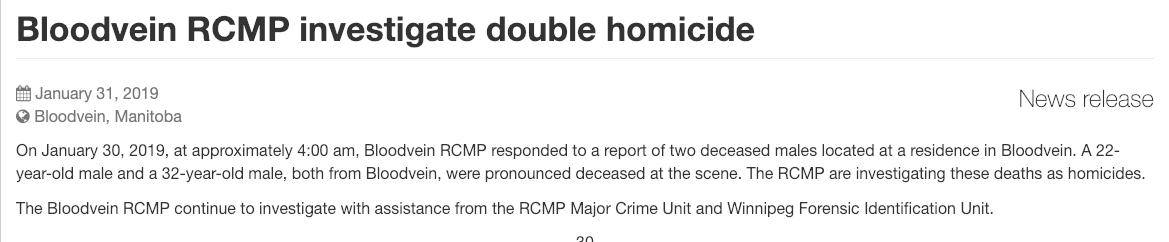

Four thousand and 17 days ago early this March 29 morning, police and paramedics rushed to a home on Alexander Avenue.

A harmless birthday party had been suddenly shot up, leaving three innocent people dead and three others critically wounded by the gunfire.

Two Indian Posse street gang members fired bullet after bullet indiscriminately into the party after kicking open the home’s back door — 19 in all.

One of the shooters, Colton Patchinose, then 18, believed — falsely — a person who had stabbed him 10 days earlier was at the party.

It was an asinine revenge shooting gone totally, madly wrong. (As if they could ever go right.)

The other shooter: a lanky kid named Joseph Jared Taylor.

Just 15 at the time, JJT became one of the city’s youngest mass killers in a couple blinks of an eye.

He and Patchinose were tried, convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Patchinose can’t ask for parole until 25 years has passed.

But things are different for JJT.

Because he was tried as a youth and sentenced as an adult under youth justice laws, parole eligibility comes earlier — Between 5-7 years after his arrest, which came two days after the shootings.

I’m here to tell you that he’s now being granted unescorted temporary absences from prison. The Parole Board of Canada authorized them, conditionally, just two weeks ago.

He’ll be in the community for up to 12 hours at a time for up to 72 hours a month. The gradual freedom he’s been earning from the confines of prison has been building up over the last two years or so.

He’d applied for UTA’s before but was turned down. That changed on March 14, parole records show.

And while the temptation to rage against this fact may hit hard — ‘but he murdered three people in cold blood,’ one might yell — there’s more to JJT’s story.

At least that’s so, as filtered through the lens of PBC documents obtained this week.

This is a tiny bit about what’s happened since he was sent to prison in 2010.

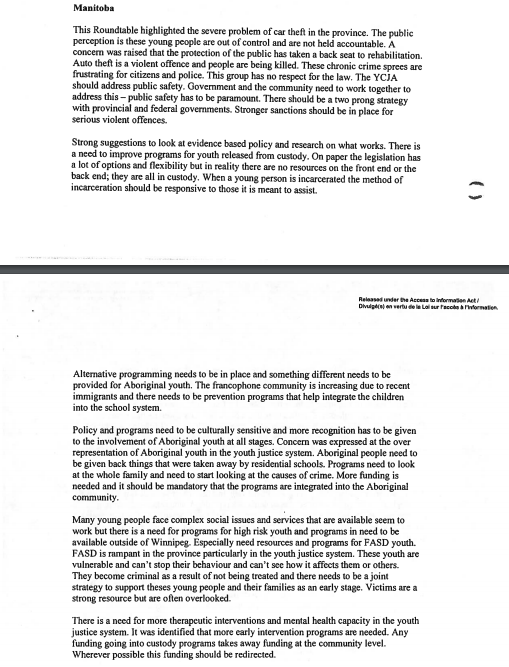

Child soldiers: A very Manitoba problem

Of the striking things that came out about JJT at his sentencing hearing, two really stood out.

His father, present in court, had little to say when offered a chance.

But his economy of words spoke volumes.

“My son was taken from me at a young age,” he told Justice Colleen Suche.

That was all he said, to my recollection.

The other thing was how the judge described him:

“…this is a story of a younger boy following older males. J.J.T.’s vulnerabilities, the absence of any safety net in his life, and the welcoming arms of gangs with their criminal culture replete with guns, turned this age old scenario into a recipe for the most deadly violence.

“It is a chilling but frank reality that J.J.T. is but one of an entire generation of children being recruited as child soldiers in the small armies we know as street gangs, which are constantly at war – with each other, and with society.”

In his most recent parole hearing, JJT spoke about his social history and how events of his background contributed directly to where he wound up.

“You discussed being educated in the street life and how you were immersed in this lifestyle from the day you were born,” wrote the two members of the PBC conducting the hearing, in which JJT was assisted by an Indigenous elder.

“You talked about tragedies in your life, including having to save your mother from an attempted suicide. You described your family as ‘broken people’ who knew no better and had no ability to be good parents or role models. You normalized substance use, violence, gang activity, crime and attempts to survive by (whatever) means available to you.”

Shoot — or get shot

JJT joined the IP at 13 in search of a sense of family and because a relative had been killed in a gang-related incident. (The gang has been described by prosecutors as the most violent criminal organization in Manitoba.)

JJT told the parole board that he soon learned the expectations of him were simple: Shoot or get shot. He soon after found his way from The Pas to Winnipeg, running drugs for the gang, sometimes sleeping on the street.

“You explained how violence was normalized in every aspect of your life,” The parole board wrote.

“You explained how violence was normalized in every aspect of your life,” The parole board wrote.

“In regards to (the shooting), you confirmed that you have limited recall as to the events of that night, but confirmed that you had been consuming alcohol and pills. You recounted travelling to the city to partake to ‘run drugs’ because that what was expected of you.

“This was just another night where you were told to do something, and despite always having weapons on your person, it was for your own protection and not intended to kill anyone. You also stated that you could not say ‘no’ to your gang ‘brothers.’ You were honest about loving the gang life and striving for status within the gang.”

When JJT was on remand, and after being sent to federal prison, things looked grim for him and those trying to manage him in the jails. He was involved in no fewer than 22 so-called “institutional incidents” in less than a year.

He instigated gang assaults, had problems with drugs and gang graffiti, and “set up a girl in a high-risk program to work with a higher-ranking gang member” on the event he was jailed.

(Those watching the news of late likely know the fates of high-risk girls are often tragic).

But then, in 2011 — something changed. At least that’s what the parole board’s records show.

He quit the IP, telling those in charge he wanted out to find a better path. It appears at least part of the inspiration for this move came from an unlikely place.

“You had even received some advice from a ranking gang member that life changes were possible and you believe that because you were interested in following a Red Road, they likely let you disassociate without a ‘beat out,’” the PBC members wrote.

Since that point, JJT has taken steps — and been granted escorted time away from prison — to have a gang tattoo removed. He’s finished high school, connected with his cultural heritage and done programming. He’s been going to AA and NA meetings. Not long ago, he joined what’s called the “inmate wellness committee” to help out in planning cultural events.

“You described your connection with Aboriginal culture and spirituality as being pivotal in your life … you demonstrated respect for protocol and the importance of maintaining abstinence ad violence-free life as a way to honour yourself and your victims.”

He was moved to a minimum-security healing lodge last August. As of November he’d completed more than 100 escorted temporary absences — including one which lasted four days to go to traditional pipe ceremonies “in the mountains.”

“You confirmed with the board that at no time have you ever attempted to push the boundaries or limits.” He considered the ETA’s a “privilege,” the board notes.

Psych evaluations rate him as a “low/moderate” risk for future violence. He’s at that same range for potential reoffending, the PBC says.

When he was denied unescorted temporary absences in the past, JJT simply kept working toward earning them, the board members said.

He’s also gotten married, to a woman he’d known as a friend, but one his probation officer thinks highly of, and who has said she’d have no issues “to communicate any concerns.”

The board granted JJT the unescorted absences — for “family contact” and “personal development” — with conditions.

While out away from the prison (no overnights) he’s to avoid alcohol and drugs, avoid “certain persons” (meaning anyone he knows or may conclude is gang-involved) and to avoid contact with any of his victims.

JJT told the board he can hardly believe he is the person who committed the murders and attempted murders.

“In your closing comments you thanked the board for their time. You acknowleged that you have taken baby steps and that this will be important as you move forward. You reiterated the importance of honouring your victims and respect the protocol as well, as the teachings have become an integral part of your life.

“While you recognize that the road ahead of you is not going to be without its hurdles, you are prepared and anxious to take the next ‘baby steps’ toward your reintegration.”

Today’s anniversary is not lost on JJT, the board says.

“On the anniversaries of your victims’ deaths and injuries, you participate in ceremony and make offerings in respect of their lives. You admitted that you have not fully forgiven yourself and that this will be a life-long process.”

Again: Time passes. Do things change? Do criminals change? Is a kid criminal doomed to a life of crime and misery — or can there be hope?

In Joseph Taylor’s case, maybe?

And although it’s cold comfort to the families of those he murdered or tried to kill — maybe there’s hope for some ounce of good to come out of the wreck of it all.

We’ll see.

-30-

Juhyun Park, 44, is accused of first-degree murder in connection with the death of his wife, Eunjee Kim, 41.

Juhyun Park, 44, is accused of first-degree murder in connection with the death of his wife, Eunjee Kim, 41. One has to give Manitoba’s provincial government some credit: they seem to love a big challenge.

One has to give Manitoba’s provincial government some credit: they seem to love a big challenge.

I’m back after a long hiatus from this site.

I’m back after a long hiatus from this site.